Wednesday, March 6, 2013

What is an Index Fund?

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Index funds: The mutual fund for most investors.

Monday, January 23, 2012

The Forgetful Investor

Today on our daily radio show Financial Impact Factor we visit elocution corner, a feature on this show that deals with a phrase or word that we toss about with great ease without any real foundation in definition. Today’s catch phrase: set-it-and-forget-it.

- “First, secular stock market cycles deliver returns in chunks, not streams." This refers to the volatility that makes news on a day-to-day basis and the fact that these swings are often much more dramatic that the overall span of an investor's plan.

- "Second, most investors live long enough to have the relevant investment period extend across both secular bulls and secular bears." This is the time span contingent that suggest that the longer you remain invested, the higher the likelihood you will benefit from those swings.

- "Third, investors do not get to pick which type of cycle comes first." Although you may think you can time the market, our emotions still play a role in how we place our goals and what, if any role the media plays in our decision.

- "Fourth, investors need to be aware that they will likely encounter both types of cycles." To this dollar-cost averaging creates a way to master the market swings by purchasing your investments over time and doing so in an even manner.

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Investing in the New Year: Are Mutual Funds Important in 2012?

This article originally appeared at BlueCollarDollar.com and was written by Paul Petillo

"Time is free, but it's priceless. You can't own it, but you can use it. You can't keep it, but you can spend it. Once you've lost it you can never get it back." Harvey MacKay

One of the key elements in any financial transaction is time. If you want to retire, you must consider the amount of time. If you want to borrow, how long you have to pay it back can be translated into dollars and cents. Investing; timing they suggest can't be down but is important nonetheless.

If you are twenty, time is on your side. If you are thirty, there is time left. If you are forty, time is of the essence. If you are fifty, time is running out. If you are sixty, where has the time gone. And older than that, time is no longer on your side. It accompanies us through life like some dark passenger. It reflect back on us from the mirror. And when we look at our retirement plan, it stares at us without guilt or shame. Time is the truth.

When I first began writing these predictions, and I've been churning out these year end ditties for over a decade, many were laced with optimism, some with an urging that we learn the lesson and move forward armed with knowledge of past mistakes, and still others were exercises in reality. In 2012, we have some opportunities and some problems awaiting us, left on the table as we symbolically turn the calendar wiping out 2011. But it won't leave quietly.

So I have a few thoughts about what you can do - resolutions of sorts but not the drastic sort we make and break almost within hours of promising ourselves at midnight.

Increase your contribution I start with this obvious chant for two reasons: you aren't making a large enough contribution and two, I would be remiss in not telling you this right from the start. And I'm not just speaking to those with a 401(k).

There are the millions of you who are forced to (and because of that are not likely to) finance your own retirement through an individual retirement account. We lament at the worker who literally only has to sign up at his workplace and doesn't. And far too often, we say little about the person who has to sign-up (after finding a fund), commit with a fortitude that is somewhat lacking and to contribute some of their paycheck via direct deposit every week or month. That effort, it seems is a much more involved hurdle.

In 2012, the investment world will be little changed. It will roil and confuse and gyrate and possibly even nose dive - just as it has for decades. It will react to news - if not from Europe form China or even the presidential elections (which ironically tend to be excellent years to invest). This will have you second-guessing your investments. But this will only apply if you have no idea how much risk you can take.

Pay attention to diversification You may not be capable of rebalancing, the act of making sure that your investments are directed evenly across many investments. This is much harder than it seems. As long as you are involved - and that is YOU in capitals - the struggle to keep balance will not get any easier.

For the vast majority of us, mutual funds will be the investment vehicle of choice. These investments will see more movement towards fee reductions. Which is a good thing. Fees will and always have been a subtraction of gains. This makes an excellent argument for indexing.

Choosing six index funds across the following cross-sections of the markets will not solve the problem of rebalancing (some will do better than others) but it will provide diversification. Index the largest companies (an S&P 500 fund), a mid-cap fund (the next 400 companies in size), small-caps (the next 2000), an international fund (an index of the largest countries (those with established banking systems even if they are currently troubled and will continue to be so in 2012), an emerging market fund (after international funds, the most risky) and a bond index (one that covers as much fixed income as possible).

Some of you will wonder if exchange traded funds (ETF) wouldn't be just as good if not better than simple indexing. In 2012, ETFs will continue to drill down ever deeper into sectors of the markets that add risk along with the illusion of an index. ETFs will become more actively managed in 2012 offering you more risk at a lower cost. Cheap doesn't mean better. 2012 will be year of the ETF. If you are unsure what these investments are, consider this conversation I had with David Abner of Financial Impact Factor Radio recently to help explain what these investments are and how they work.

Focus on your financial well-being This refers to your credit score. It continues to impact your financial future and will become increasingly harder to ignore. A new credit rating service agency will add to the difficulty in 2012 and not only will the current scoring impact costs such as insurance, it will seek to trace the breadcrumbs of your financial life more thoroughly that the big three do.

There is little likelihood that the job market will increase as many of our returning troops will flood the marketplace, taking numerous jobs from your kids just out of college. Which means another year with your kids at home. The only answer to this problem is to continue to tighten down your budgets in 2012. As I mentioned earlier: "If you are forty, time is of the essence. If you are fifty, time is running out. If you are sixty, where has the time gone."

And you must do this understanding that inflation - not the reported number but the real number in your grocery bill - will still chip away at your wealth. This means you will move in two opposite directs in 2012: saving and investing more for your fleeting future (at least 6% but 10% would be best) and spending less in the present (easy of you don't use credit).

And the housing market will improve for those who have repaired any damaged credit or who have saved enough of a down payment to buy a house. people are still buying and selling. These people have found that while the market is not accessible to all, it is for those that have done right by their personal finances.

Do all of that this may not seem like a new year - but it will be a better year!

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Mutual Fund Investing: Can You Be Blamed for the Global Crisis?

Saturday, July 2, 2011

Mutual Funds and Performance: At the Half Way Point for 2011

But you would have been much better off had you done absolutely nothing. Back in those desperate times, many people did what the rest of the herd did as stocks began to tumble. You sold. But three years later, that would have proved to be the wrong thing to do. During that period, most folks fled the actively managed mutual fund, particularly the domestic issues in favor of bond funds and in far too many instances, to target date funds.

Let's consider the indices that are often compared to the riskier funds, a benchmark that has proven to be less than accurate in terms of performance. The Dow and the S&P 500 track the largest companies, a group that has struggled to assure the investor that dividends and size were enough to best the market. Turns out, that picking and choosing, as actively managed funds do, would have been the better approach.

Two things come into play. One, these funds tend to have higher fees. Less those fees, you would have still found yourself in a better position than had you simply put your money in a benchmark S&P 500 index.

And secondly, there is the liquidity issue that comes with buying mid-cap and small-cap companies. Liquidity refers to the amount of stock available in smaller companies weighed against the amount of stock held by the principals. This makes these companies more volatile and even under-purchased in indexes that track those larger markets (the Wilshire 5000 for instance may track all available stocks but the indexes crafted based on this index only own.

To complicate matters somewhat, the Wilshire 5000 actually has 5700 stocks in the index, Wilshire 4500 is the Wilshire 5000 without the S&P 500 stocks in it. A Wilshire 5000 index fund (usually called total market index) will probably own around 4000 stocks. A Wilshire 4500 index contains those same stocks less the top 500 companies.

As Mark Hulbret noted in a recent column for Marketwatch, "According to a report produced earlier this week by Lipper (a Thomson Reuters company), 45% of the domestic-equity funds for which they have data back to October 2007 were, as of the end of May, ahead of where they were on the date of the stock market’s all-time high."

So the indexes are lower than where you would have been had you stayed put - of course this is based on the assumption that many of you where using actively managed funds in your 401(k) plans, that many of those funds did not have indexes available and the post 2007 products such as target date funds or even ETFs, weren't a consideration or even an option during those days. You embraced risk and ignored fees and looking at your portfolio, that was probably seen as a good thing.

Does that mean index funds shouldn't be part of your portfolio? The simplest answer is no. Index funds still provide a low cost and low turnover environment to invest in. More importantly, the largest cap indexes add dividends to the mix. This brings these investments closer to the domestic out-performance over the last half of the year.

Diversity in this investment environment, which is still far more volatile than anyone would like it to be, with global issues remaining a major concern, means taking a little less - in terms of performance. You should be in index funds now. To do this would be considered a defensive move for those that kept the actively managed faith.

A portfolio of five, perhaps six index funds, tracking sectors from the S&P 500, a mid-cap index, a fund tracking the small-cap, an international index (which tracks the companies of what is considered the developed world), an emerging markets index (contains investments from countries like China, India, Russia, Brazil and others) along with a bond index. This sort of diversification keeps the low cost features of index funds and avoids any crossover investment (owning the same stocks in different funds).

You can be proud of your investment accumen in getting back to those 2007 highs and perhaps beyond. But show your real prudence and protect what you have done. This economy, both domestic and globally is far from recovered and the stock market is painting a better picture than reality suggests. Being a little defensive at this juncture will keep you in the game without risking what you have gained.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

The Plight of the Savvy Investor and the Goldilocks Mutual Fund

And perhaps the first emotion we feel once we begin to second guess each of our "investment" decisions is regret. And if the recent selling of actively managed mutual funds by investors over the last year or so is any indication, regret for past decisions is in full swing.

Adding to the chatter that actively managed mutual funds and by default the managers who stand at the helm, is John Bogle, chanting the mantra he has carried since the late seventies. Why, he has asked, would anyone choose to look for more than what an index fund can provide? And as we begin to acknowledge the pull and tug, feel the most susceptible to such cost savings as a lower fees, which is always good, index funds begin to come to the front of our thinking about which investment is best.

But once you begin to believe that getting mediocre returns in the equity markets is the "new" goal, the attempt at saving some money in terms of the fees charged by actively managed funds in exchange for the smaller returns that index funds offer becomes the overall focus. And if that is the sight path you choose, index funds are definitely the right fund to use.

In a recent report in the NYTimes on the subject of this exodus from highly regarded performers over decades to index funds in search of lower fees, one thing stands out in the numbers. This is simply a beast feeding upon itself.

Consider this: You own X amount of shares in an actively managed mutual fund and you sell. But rarely do investors act alone. They are signalled by some change in the wind, some report drilled over and over or perhaps, it is from the suggestion of a colleague. Suddenly, fear sets in and you begin to think that you have the wrong investments. The fees are too high, you think and then anything that resembles a stick snapping alarms you and your fellow investors and you run. And then you regret.

The selling prompts the redemption of shares, which when enough investors sell simultaneously, and enough shareholders accounts need to be made whole as they leave, markets move. And if the movement is great enough, the equities drop. And so do the indexes. So you sell at a loss only to buy shares in a fund you just, via the herd, lowered.

In many instances, the outflows are no reason to believe that the actively managed mutual fund world will implode. In fact, according to Brian Reid, the Investment Company Institute’s chief economist, 93% of the investment assets stayed right where they were as the remainder moved to other investments. Among those investments - more than just index funds reaped the benefit of this change in loyalty to actively managed funds - overseas funds gained as well as funds focused on commodities. Bond fund outflows also helped boost the index fund profile.

And what did this sell-off net the exiting investors? What were they looking for? Believe it or not, index funds that are actively managed. This surprising move has some folks, including myself, scratching our collective heads.

True, the fee structure of index funds is far cheaper that that of the actively managed fund (index funds average about .16% while actively managed funds average about .97% - with many load and closed end funds added into that average and increasing it as a result). But once you let a broker enter the mix, the fee structure changes, coming closer to the cost of the actively managed fund and at a lesser overall return.

Index funds because of the tax efficient structure belong in taxable accounts - as long as the capital gains tax remains historically low. Inside a tax deferred account such as a 401(k) or an IRA, the effect is lost. This is and should be the domain of the actively managed mutual fund. And while you should never lose sight of the role fees play in the long-term performance of your investments, believing that fees are the only driver in achieving steady returns is misplaced.

And while I have nothing against index funds, the growing number of funds that slice and dice the markets do not always lead to lower fees for investors. But talk about index funds enough, and investors won't notice nor take the time to compare one index to another.

Thursday, March 24, 2011

Hope for the Best: Picking Mutual Fund Winners

Now I have mentioned here before, this is a less than perfect way to determine success. But it is all we have. No actively managed mutual fund owns, in the same proportion, the underlying portfolio of the index fund. Index fund advocates suggest that index funds offer the wide diversification needed to get investors from point A to point B and do so in a passive manner.

Actively managed mutual funds do something quite different. And investors who use them know this. Investors looking for just a little more from their investment dollar believe that there is always the chance that the fund they pick will outperform the index fund benchmark. Few do. But the effort is worth the gamble. So why is it that we look backwards in order to move forward? Is what happened important to what might happen?

When an investor buys an actively managed fund, they have two choices to help enable their decision. The first is what the focus of the fund is. Understanding the underlying investments, how the manager approaches the fund's individual charter, how often the fund needs to readjust to complete that task and whether the fund manager can accomplish this in a cost-effective manner all play into the decision of whether or not to buy in. These are forward looking mechanisms designed to give us some level of expectation.

The second tool we use in the decision making process uses the exact opposite methodology: where has the fund been. By no means is this a necessary tool. Yet it is often employed by index fund advocates to point out the error of the actively managed mutual funds. Based on where these funds have been, indexers point out that had these same investors used an index fund, they would have been better off.

But this is not why people invest in actively managed funds. They do so to fulfill some inner need to do better than average. So why if that is this case, do these same investors, who see themselves as better than average and more savvy than the rest, look in their rearview mirror to get some indication of what the road ahead holds for them?

What was will never be again. None of the fund screeners offered around the web, from CNBC's to Forbes to the brokerages to the Persistence Scorecard offered by the Standard and Poors give you any idea whether the fund you are considering will do good in the next quarter, the next year or even the next ten-years. In fact, all of these screeners suggesting who won in the previous time periods would be useless in picking the next benchmark beating fund.

There are several things to consider when looking to invest in an actively managed fund. At the moment right before purchase, every one is on equal footing. This is referred to as the initial opportunity set. Every fund manager is equally skilled and/or prone to the same luck. The differences lie in the cost of the fund in terms of administrative costs. This is somewhat similar to suggesting that every horse in the race has four legs.

Yet unlike a horse race, where lineage, training and numerous other factors come into play, at the beginning of the race, all mutual funds are essentially equal. Once the new quarter begins, the race is on to beat not only what the benchmark might achieve but what other funds might do as well. At the end of the race, unlike horse racing, the gamblers place their bets. Sounds odd when considered like that, but it is essentially what happens. When the quarter is complete, new investors look for the winners, something that has already occurred and buy in.

The S&P Persistence Scorecard suggests that you will be right about 25% of the time employing a method of picking past winners over the previous five years (a period that seems to be quite a long time). You would have done slightly worse trying to pick a long-term winner amongst the mid-cap sector; slightly better with a small-cap fund. What the Scorecard does not suggest is the shifts among the stocks in the small cap to mid cap to large cap arenas during that period depending on capitalization (a shift that can change with each bull or bear market, mergers and acquisitions or simply with bankruptcies).

In fact, the Persistence Scorecard suggest that the middle of the pack might be a better indicator of what might come. If the top quartile is predicted to not repeat and the bottom quartile should be not considered as potential winners in the future (most at the bottom of the scorecard will probably merge or be liquidated in the future because of this underperformance), that leaves the second and third tier funds as the next winners.

If past indicators tell us anything, it might be to look the other way. Or, they might suggest that last quarter's average will be the next quarter's winner. Whatever it is, some skill and a lot of luck keep the current winners at the top of the rankings. Which is why few do with any success. If you are picking your next opportunity based on what happened, you would be better off with an index fund. I say this because average in the actively managed mutual fund world is a bit more expensive than simply buying the index.

But if you think you know the future, your ability to pick the next winner will make the envy of your fellow investors. And considering the odds, you have about a one-in-four chance of doing so.

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Is Average Good Enough?

And that's fine. An index investors is supremely confident that all will be well with their investment choice. The fact that they were able to purchase it for far less than what the actively invested mutual fund charges and that argument is always pointed out in every conversation about index funds makes the debate somewhat one-sided. Yes it is true that buying something for less is advantageous when it comes to investing. Low turnover (index funds readjust their holdings when the index they track changes) mean lower taxes (an interesting event because index funds sell losers and buy winners when they do readjust) and the combination of all of this seems to satisfy even the most average investor.

But I'm not so sure that actively managed mutual fund investors consider themselves average. Nor do they pursue such a state. In large part, because they already have it. As I mentioned earlier index fund investors like the concept of average. They embrace the inefficiencies in the market and defer the thinking about where the market will move next to the idea that spreading the risk is far more essential to protecting the underlying investment. But that protection comes with a cost.

If index funds are so much better for the investor than those of the active sort, why aren't these the only investments in use. When you look at the differences in investment styles, you find that index fund investors tend to only own index funds whereas actively managed mutual fund investors own both.

Perhaps it is the very nature of index funds. Where in almost every instance, the traditional index fund is employed, the reality of how these funds allocate the money, with the 10 companies in the index usually garnering the top 20% of the indexed dollars might lead those active investors to think that there is a chance that the remaining 490 companies in a typical S&P500 index might offer something of an opportunity.

Investing outside of index funds had been referred to investor ignorance. Betting against what are seemingly long odds of success has a certain attractiveness to the process. Call it the "what if" approach. Back in August of 2010, Lubos Pastor of the Chicago Booth School of Business and Roger Stambaugh of the Wharton School of Business wondered why do actively managed investors continue to chase these funds when the statistics offer evidence that the returns in these investments will be subpar.

To invest is to embrace the knowledge that in every investment there are two players: the one with the reason to sell and the one with the reason to buy. Trusting that a fund manager can determine which is the better side of that purchase is why actively managed funds remain more popular than index funds. True, few are skilled enough to find that pivot point but the professors have found that movement in and out of these funds, based on decreasing performance might have something to do with why they stay in these funds at all.

These investors, at least according to the professors take dispassionate rather than long look at where a fund is headed and readjust their investments accordingly. Nathan Hale of MoneyWatch believes that it instead "represents a fundamental misunderstanding of how investing works". He argues that even though actively managed investors think the additional research they do, the faith in those that they have hired because of their expertise and the fact that they have to work harder to get the returns needed to keep investors investing, Mr. Hale writes that this will "inevitably detract from the returns you earn in the markets".

As long as the comparison of performance is skewed - benchmarks are always used when comparing the two types of investments when few if any actively managed funds hold 500 stocks in their portfolio - the proof of who is right depends on how fully you embrace the concept.

Active investors don't suggest that indexing is wrong and may have been the result of an increase in net inflows to index funds over the last several years as they moved to protect some of their portfolios. They just believe that the opportunity to do better is worth the cost, adjusting their holdings to react to lack of or increased opportunity. Mr. Hale sees this shift as the embracing of index wisdom.

Is it a "recognition of the benefits of an indexed approach" as he suggests? Or is it perhaps the simple fact that using actively managed investments are more involved, intellectually stimulating and make the investor feel like an investor? Is it an understanding that to live as a investor (using every means possible) better than simply chasing average?

Use of index funds will increase as new investors come into the marketplace, uneducated or perhaps under-educated. Auto-enrollment may add to the involvement. The use of these funds by Baby Boomers looking for some equity allocation in the final years of their work-life, realizing that some exposure is better than none may also contribute to the increased use of this passive investment. Time will tell. But actively managed mutual funds, even though maligned by index investors, will always be available to the investor.

Wednesday, February 9, 2011

Are Actively Managed ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds) Worth a Look?

So we have one group who "invests" and the other who "save".Both use essentially the same tools and with any luck, practice the same prudent practices. Tempting both groups is the ETF or exchange traded fund. When these we first introduced, about a $1 trillion worth of investments ago, they were heralded as the one thing investors needed to keep their assets where they could get to them, when they needed them.

Trading like stocks, you could buy an ETF in the morning, sell it if you wanted to at noon, and buy it back before the end of the day. This was a genius move on the part of Wall Street and began generating buckets of cash via trades. Mutual fund companies wanted a piece of the action and jumped in as well with ETFs that looked eerily similar to index funds they were already selling.

The cost of the trade was about the only thing you could toy with. So they eliminated that fee. But not to be allowing you to do something for free, they found another way to charge you. Back on January 6th, 2011, I wrote: "a Vanguard spokesman said the company believed “that the ability to attract and retain clients, particularly high-net-worth clients, will improve the bottom line and ultimately result in lower fund expense ratios.” The truth is that instead of charging for the trade, they charge you to hold the ETF in your account."

Now, three years into the first appearance of the actively managed ETF, we wonder if this will be as wildly popular as the indexed ETF (which has sliced and diced the market in such a way that no corner of the investment world is un-indexed and because of that, has added to the volatility in the marketplace, particularly at the close of trading). Perhaps but the wary investor and more than one "saver" should approach these tools with caution.

Does an actively managed ETF cost less than a actively managed mutual fund? The short answer is yes. Mutual funds bought outside of your 401(k) - where fees tend be lower and in some cases, different - have fees for distributions and marketing. While these fees are annoying and do take away from your returns, they are needed to attract new investors, pay for research into which stock is next on the buy or sell list and to pay for the services of the fund manager. Could they be lower? Yes. Have they dropped significantly? Over the last several years, yes. But what about their ETF counterpart?

Without many of those "trailing fees", actively managed ETFs are less expensive. But few people add in the cost of the trade when they think of purchasing an ETF and each time you buy or sell, this acts as a fee - albeit right up front.

Several other comparisons come to mind. The transparency of ETFs, which must disclose what they hold everyday seems on the surface like it would be a grand idea. But when it comes to this type of investment, transparency and rules for trading tend to make this a dangerous place. In an index fund or ETF, the investments mimic an index, set and left alone for a year, sometimes longer.

In an actively managed ETF, which discloses its holdings and must disclose its building or restructured portfolio almost as it executes the trade, it allows investors outside of the ETF to "front-run" the fund and buy at a cheaper price than the fund would pay. This is not good for the ETF manager if the stock they are buying is somewhat illiquid.

Taxes are another issue. Mutual funds tax you quarterly and yearly. Index ETFs tax you only when you trade them and because they don't turnover (trade their securities often) as much, the taxes, once levied are less. Actively managed ETFs only charge you taxes when you sell the fund but, because they trade often, the taxes you will pay will be higher than indexed ETFs.

Now there is little I can say that will dissuade you from buying an actively managed ETF once they become more widely available and have logged a track record (currently, they have less than three years under their belts). If you find them in your 401(k) and they are cheaper than actively managed mutual funds, they might be worth looking at if you are looking at adding some risk.

This investor tool is not going away. And it will add to some additional volatility as traders in these funds move around much more than those that hold individual stocks and/or mutual funds. And that can't be good no matter how you view who you are: and "investor" or a "saver".

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Mutual Fund Investing: So what are mutual funds and how can they improve your life in 2011?

So what are mutual funds and how can they improve your life in 2011? There are only two types: actively managed or those indexed to a specific grouping of investments. From there, it gets complicated but getting from there is where the whole traffic jam of ideas begins. It makes no matter, which school of thought you ascribe to if you do at all: everyone needs and actively managed group of mutual funds and a passive group if you expect to do anything worthwhile in 2011.

In the coming year, one which is predicted to be quite good despite my doubts, which I will put forth in couple of days with my year-end look at 2011, diversity will deliver more than simply chasing one ideology of the other. The "indexers believe that these sorts of funds are all you need to succeed in any year. Offset by relatively low costs, these funds make up for hoping that that through diversity they can achieve better than average returns for those who invest in them.

As a group, index investors are a fervent bunch. They espouse this investment as the be-all-to-end-all tool and in doing so, give those who chose the other camp - the actively invested mutual fund - to wonder if they may be right. There are reams of research that indexers point to as the reason why they believe this approach. But passively sitting back and letting the market determine your investment outcome is not for everyone.

Actively managed mutual funds are structured in the same way as index funds: a portfolio of investments (stocks, bonds or both), a manager (be it one, more than one or a computer), disclosure and regulatory rules that they must abide by, and performing as billed, if not better. The difference in who picks what is in the fund. Index funds are determined by an index published by such notables as Standard and Poors or Russell or Wilshire. Actively managed funds contain investments picked by management.

Both bring like-minded investors together to pool their money and in doing so, offset the risk and cost of having to build a similar portfolio on your own. Actively managed funds try and outperform their index counterparts in large part because it is these indexes, right or wrong, in which their performance is gauged and graded. If they do better than an index, investors notice, add their money and create increased opportunities for the fund manager to increase those returns with additional acquisitions.

It doesn't always work and some comparisons are unjust (how can you compare a fund with fewer than 100 holdings to one where 500 are held?) and do not paint a true picture of performance. But in tandem, they might work for different reasons for everyone interested in a more profitable 2011.

In times of turmoil, everyone feels pain. When the whole of the marketplace dropped precipitously in 2008, no investor escaped. Some were damaged more than others but as a group, we all felt pain in some form almost at the same time. Investors who simply plowed money into a 401(k) or loaded up on their own company's stock and thought that investing was a world of do-no-wrong, were given a rude awakening. Those that traded actively on their own and were beginning to feel some invincibility creep into their results were caught unaware as well.

And in the past year, investors in US stock funds did what they had done in the previous three, withdrew more than they invested, Called outflows, they impact mutual funds harder than the selling of shares from your own portfolio. These outflowing funds are produced with the sales of a portion of the portfolio. And every such move impacts the remaining shareholders in the mutual fund.

Inflows, or your money pouring into a mutual fund comes automatically in a 401(k), through deductions into an IRA and self-deposited by individual investors. Yet only a handful of people I speak with everyday likes the idea of a mutual fund as an investment and if last year was any indication, think fund focused on the US stock market alone is not the path to financial success.

Why? We want simple things to work extraordinarily well. Nothing does but we expect it of mutual funds. We want low fees, we want moderate risk and we want to know that our money is safe from market interruptions and taxes. And at the same time, we want growth, to retire early and to have our investments perform without hiccup for decades. Only mutual funds can do this - even if we dislike the idea.

Low fees, moderate risk, safety and tax efficiency is a tall order with three of the four fitting the index fund bill. Safety is subjective and safer, even more so. But no equity index fund alone can do this. No bond index fund alone can do it either. Target date funds, hybrids of other equity and bond funds (and often a basket of such funds from the fund family) promise all of the above but have yet to prove they can deliver.

Yet three out of four isn't bad. Put this type of fund in a Roth IRA and put as much as you can in it, consistently over 2011 and you will do as well as this year has done (which looks to be two back-to-back years of double digit gains for the S&P500 index). Even if you do half as well as the 20% plus gain in 2009, you'll be way ahead of where you'd be otherwise.

In the other group, looking for growth, outsized returns and freedom from hiccups, look to your 401(k) where your employer may be retuning to offering a match in 2011. If they do, this is not so much free money as hedged money. A 6% match added to your 6% contribution gives you a lot more room to assume risk that you probably are. Retiring early is a dream even as we acquiesce to work longer. But it can be closer to a reality if two things happen: you invest more and use actively managed funds in your 401(k) to get there and the market corrects a little in the first half of the year. This means buying more for less and positioning yourself for a good 2011. Not 2010, but close.

Whatever your outlook for 2011, a tandem approach to investing - using index funds and actively managed mutual funds might be the best approach in the next year. Be cautious of only two things: this isn't advise and be careful you don't over-expose yourself in any one sector.

Monday, November 15, 2010

To Index or Not: Mutual Fund Investors still ask

Which leaves the actively managed mutual fund investor, often described as a resident of Lake Wobegon (where everyone is above average) as the beneficiary of this shift ininvestment style. The question that every index fund investor will ask every opportunity they get: how do you pick an actively managed mutual fund if so many underperform?

And it is a good question. But the problem is, how do you make that call if you are essentially comparing these sorts of funds to those that buy across a broad market? An index fund, for the sake of argument we'll use the S&P500 index as an example, buys the top 500 companies. These companies are in the top 500 due to market capitalization. But index funds don't buy all 500 equally, weighting their funds based on numerous criteria.

Among those are as I mentioned, market cap. To be eligible for this index, a company must have $5 billion of market worth (issued stock) with 50% of that stock available for the public to buy. They must be based in the US - it doesn't matter where they do business as long as the headquarters are on US soil, follow GAAP reporting practices and offer sector representation.

The weighting of an index like this, which many investors assume is done much more evenly, actually gives the top ten companies based on market cap, over 20% of the index, leaving the 490 remaining companies to fill out the rest of the index. How would this sort of style compare to a actively managed mutual fund that owns less than one hundred stocks in their fund? Talk to an indexer or as they often refer to their group as Bogleheads, after the man who brought the index fund into existence (there were attempts made earlier than Mr. Bogle's but the ability to do it correctly was dependent on the advent of the computer) and they would quip, there is no comparison.

Yet, this is the very comparison they make, time and again. Their argument does hold some merit. Index funds have lower fees because they trade only when the index changes. (This is an irony lost on many indexers as the these funds must divest any interest they might have in a stock taken from the index and purchase any security the index has added - a sort of counterintuitive move of selling losers and buying winners.) Many still charge 12b-1 fees even if they are in company sponsored plans and act as the default investment. Over five years, performance of the S&P500 index has been north of 15% and that was due to the large amount of value given those top stocks in the index and the dividends paid by many of these large businesses.

Actively managed funds do have more to contend with in terms of trading (more frequently but the best funds do so prudently without changing their whole portfolio in a given year) research (they aren't given a group of stocks to buy as the index publishers do) and their are management fees (the cost of hiring a professional to wade into the marketplace for you). Yes these do impact the overall returns of a fund and as investors focus more on these items, they have dropped significantly in recent years.

So what do you get with an actively managed fund that isn't there for indexers. Obviously, a bit more nimbleness, less buy-and-hold and if your fund manager is good, acceptable returns. Most investors do still look to the performance - and too often in the short-term, as in a year or even a quarter just past - as the tool most likely in their portfolio picks. Doing this at the exclusion of tenure - how long the manager has been at the helm - the fees - they should be low, under 1% with a portfolio turnover in any given year of less than 60% - and should be able to best their peers in both categories, if not the index they are often compared to, over five years or longer.

Indexed funds have pluses that seem outsized compared to actively managed funds. But too often, a one size fits all approach to investing is not suited for everyone and this is where actively managed funds fill the void left by that sort of approach.

Friday, October 15, 2010

More than Just Mutual Funds: A Peek Inside your 401(k)

Just get behind someone at a fast food drive-up window and wonder how long does it take to order from a menu that rarely changes. Your 401(k), the defined contribution plan that many of us have, puts us in the retirement planning drive-up lane and forces us to make a choice.

Few people ever decide to drive on through without making a selection. Once in the line, you are sandwiched in by the person in front of you, the car behind you and the prohibitive curb. This is your 401(k). This is your 401(k) menu. Order now, pick-up at the second window, pay at the first and be satisfied with your choice in large part because there is no going back, no changing your mind or adding something else on to the pick you have made (without exiting your vehicle, which defeats the whole purpose).

This is where almost every 401(k) plan in this great nation fails. Once you have been put in the drive-up lane, you are stuck. You are essentially given a select number of choices, many of which are easy to determine how much they cost in part because your plan is now loaded with index funds, which basically resembles your dollar menu. Cheap and (portfolio) filing without a lot of extras.

Then the seniors portion of the menu, also bland (and bond-like), suggests that you can get value from your invested money by making sure you get your dollar back - or at least in theory. The kids menu has gotten smaller over the years your plan has existed because there is fear that if this portion of the menu were too large, you might find the restaurant liable for (actively managed mutual funds) choices that were too expensive and fraught with risk. They could throw in a toy but you would want proof that you could purchase this item without ever being dissatisfied.

So they offer you menu items that you wouldn't expect. These are items that would be better suited at a sit-down establishment where the big spenders go - not because they want to spend more, they just want to think they are more sophisticated than the general population. This is the ETF (Echange Traded Funds) choice.

And then we have the value meals. This portion of the menu dominates the process and in effect, bogs most of the line down if there should be someone who is indecisive. These are your target date funds, a combination of mutual funds tucked under one banner which suggest that you can pick a year in which to retire and the item you choose will not only be worthwhile, but will also fulfill its promise.

Everyday, folks drive up to their 401(k) plan and are forced to make a choice. Everyday, your 401(k) plan is scrutinized by regulators. Everyday, 300,000 advisers go out to the field and, well for lack of a better word, advise. That's 300,000 different drive-up windows, sponsored by just as many employers for millions of employees. A daunting task indeed. Which is why you are dissatisfied with the choices: you think that there is a better drive-up window someplace else.

Of those 300,000 advisers, the vast majority of them, according to Fred Barstein, the president of 401k Exchange "half have one employer plan. Half of those have at least three plans. Fifteen thousand or so, or about 5%, have at least five plans. Then there's the 5,000 or so elite advisers, who have at least 10 plans, $30 million and at least three years experience." Mr. Barstein, who is also columnist for the Employee Benefits Adviser site, suggests that the fees that these advisers charge have dropped significantly in the past several years, which is good for the participants but makes it doubly difficult to make a living doing this sort of work.

Not only is the competition stiff, the drive towards least expensive and lowest risk has sliced the revenue stream in half. You might think this would be good for you, the 401(k) plan participant. Turns out, it hasn't been as good as you thought it was. In this particular scenario, these sorts of plans have become more generic, less customized and inelegant.

When an adviser approaches your employer, the sell goes something like this: You want almost zero liability, almost zero costs, and near zero effort on your part and I, the adviser, will do this by offering target date funds and perhaps a huge basket of index funds and, if we can figure out how to squeeze one in, an annuity. None of these offers your employees any guarantees, the adviser might suggest ,except for the annuity, which illustrates a distribution of retirement income and unfortunately comes with a cost (a trade-off of sorts).

Is it any wonder why you sit at the drive-up menu for longer than you should? All of the choices look the same. And then there is the problem of getting you to order the product best suited for you. Here is where they suggest a sort of buy one get one free (or the matching contribution). By the time you get to the drive-up window, you may been sitting in line, waiting your turn for almost a year. Then to get the other half of the buy one, get one free offer, you may have to wait an additional period of time (a vesting period that can be more time than you planned on staying with the company to get).

Then there is the super-fast lane where you are essentially put on a bus, driven through without access to the window at all. The driver, your employer in this example, orders what they believe is best suited for you - take it or leave it. In this situation, you will be dropped into a target date fund and told that you can opt out (go hungry) or stay in and believe that this menu choice is probably the best one for you because someone thought it might be. That someone is the adviser.

Now Mr. Barstein does suggest that at its rawest, it is about selling. Selling a plan involves training, partnering and a constant source of information. Much like fast food drive-up windows, who might consider your health as a passing interest in order to get you to come back, increase their bottom line with a salad and offset fears that their choices are not the best ones available (doing it yourself will always be more satisfying but more time consuming as well), your 401(k) plan is designed to fill you up.

The adviser and the plan sponsor hope you drive off happy and satisfied. As long as you drive off and don't sue them.

Monday, October 4, 2010

Keeping that Balance and Maintaining It: Asset Allocation

Asset allocation is something of a mystery to most of us although no writer worth her/his mettle would bypass the opportunity to tell you it is one of the keys to investment success. You will hear those who use index funds as a primary driver in their portfolios selling the notion that once you embrace this passive sort of investment, asset allocation becomes second nature. It certainly becomes easier.

To allocate assets is to take and spread risk across many different stocks and bonds. The idea here is that no market performs in tandem. Some corners will remain sluggish while others shoot for the moon. Asset allocation keeps you in both but keeps you involved in a measured way.

Too much of any asset class usually means that asset is doing really well. This is where the tough part comes in. If that asset is doing so well, you probably should begin selling some of it in favor of the assets in your portfolio that aren't doing so well. This sounds sort of counterintuitive and I'll explain why it shouldn't. Even if afterwards, it still does.

Because we are talking mutual funds and not individual stocks, and we will for the sake of the argument, use index funds as an example. A large cap index fund may be in favor with investors because investors are looking favorably upon the companies in the index. But you also hold an index of small-cap companies that seem to be lagging behind - at least as a comparison. To continue to send money to the ever-rising fund, you should take some of the profit off the table and transfer it to your other allocations, balancing your investments at the point you began.

But, you stammer, that fund could go higher. Why sell a winner? Because that is what you do to make money: sell winners. But in order to keep your allocation in balance you shift those dollars to the other funds in your portfolio, buying shares in those funds when they are less expensive.

Should you consider using actively managed funds in this process? Depends on your age and whether you plan on focusing on the balance among the funds in your portfolio. If you have a fifteen year or longer time horizon until you estimate you will begin to tap your account for income, feel free to take your chances.

Index fund users will never stop stressing the importance of fees and the low cost index funds have. And this is important. But fans of the actively traded mutual fund are also focused on fees and equate performance against this measure. But the comparisons are difficult and calling this type of investing successful depends on numerous variables. (From which benchmark is being used to how many funds are spread across how many asset classes, the variables can astound and compound.)

The importance lies in keeping that balance and maintaining it. The only risk you can add to your portfolio is not adjusting your allocations at lest once a year. We are in for a volatile decade, as unemployment strings out, debt continues to be an issue and the tax debates continue and that is not without some pressures in the stock and bond markets. This balancing act wil take time and effort. But the person who bothers will end up with more years of positive returns than someone who fails at this decidedly unsexy task.

Saturday, January 9, 2010

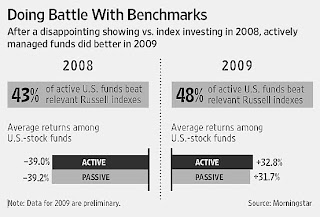

In any given year, a handful of active mutual funds will do better than the benchmark index fund. And investors are usually warned, and I obligated to as well, that what is hot today or last quarter, even over the past year in all likelihood will not be so after you invest. This is why it is always recommended to look much further afield, at least five years, ten is even better see how well a fund has performed.

Should you switch your investment style in your retirement portfolio as a result? Read more here.

Paul Petillo is the managing editor of Target2025.com.

Monday, January 4, 2010

Resolution Time: Fixing a Few Bad Investment Habits

But with little effort, you can change how you invest. For the vast majority of us, investing requires far too much time. It requires continued education (which I fully recommend), frequent monitoring (which can involve little more than opening your statement just to make sure your investments are going where you intended) and a clear-cut understanding of where you are on the timeline (beginning to invest or at it for awhile).

Altering bad investment habits is not that difficult. Five Tips for 2010...

Paul Petillo is the Managing Editor of Target2025.com

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Mutual Funds Explained: Topic of Fees

In our first discussion about performance comparisons for mutual funds, we looked at the downside of simply comparing side-by-side an actively managed fund with one of the indexes that are published. These indexes span a wide variety of categories in order to help investors understand how the broader market has done in relation to the fund they own.

Trouble is, no fund, not even index funds are able to buy in total, all of the stocks in a particular index. Yet, index funds are designed to come as close to the index they mimic. Any wide discrepancies, either higher than the index or lower than the index should raise a warning sign to current and new investors. This could point to a style drift, a process whereby the fund manager looks to stocks outside the parameters of the index to beef up returns. because in the world of mutual funds, one-hundredth of a percentage point can often sway the investor's decision of which fund to choose.

Often, this focus on returns drives the investor to funds that are the wrong ones for a long-term approach. Even almost five years since the publication of the paper b the Wharton School :"Why Does the Law of One Price Fail? An Experiment on Index Mutual Funds," by Madrian, James J. Choi, professor of finance at Yale, and David Laibson, economics professor at Harvard, folks still do not adequately take these costs into account.

In their experiment, they used index funds as the sole investment. The S&P 500 index, which tracks the 500 largest companies trading on the US exchanges should all have identical returns over the same period. The only difference lies in the fees the fund charges the investor. These fees are often touted as the lowest available and with good reason. The investment itself is passive. Managers buy and hold any underlying stocks in the portfolio until the index itself is readjusted.

Their concern before the experiment was based in the question: why, if index funds outperform actively managed mutual funds most of the time when held over long periods of time, such as twenty years or more, would an investor pay higher fees when index funds charge so much less? They pointed out that when an investor considers fees to relative performance, say when an actively managed fund matches the returns of a passively managed index, the investor will not consider fees as an important factor in the process. If both of the funds in this paragraph earned the same 10% over that twnety years, the difference in real dollars would be over $11,000.

To conduct their experiment, the chose only four funds, all S&P 500 index fund. They all varied slightly in overall fees with the performance of these funds almost identical. They could invest all of the hypothetical $10,000 in one fund, or divide the investment among many funds. The reward for outperforming their cohorts was an actual cash prize: the profits generated by the best performance over the course of a year.

They broke the students in the experiment into three groups: one received a prospectus accompanied by a returns sheet, one a prospectus accompanied by a fee sheet, and the last group, the control group, received only a prospectus. In each case, the prospectus was the same as the one any investor might receive upon request.

The result of the experiment indicated that disclosure did have an effect on the students in all three groups. The group with the returns sheet did the worst. Those that received fee information did better. What was most curious about the results: the students with the fee sheets could clearly see that one fund among the four offered the lowest fees yet not one student put all of their money i that fund despite the relative identical natures of the overall investments.

By no means does this say that fees are or should be the only force in your decision to buy a certain fund. But they should enter into the discussion at a much higher level that that of overall performance.

Next up, the role of the manager.

Paul Petillo is the Managing Editor of Target2025.com