For the vast majority of investors - mutual fund investors in particular, watching the major indices and judging your performance against them distorts the reality of not only where you should be but where you could have been. If you were to look only at the difference between the former highs the markets hit in October 2007 and those at the most recent close on Thursday (the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA +1.36% is around 12% below its all-time high of 14,165, and the S&P 500 index SPX +1.44% is nearly 16% below its October 2007 high of 1,565.) you might be considering jumping back in.

But you would have been much better off had you done absolutely nothing. Back in those desperate times, many people did what the rest of the herd did as stocks began to tumble. You sold. But three years later, that would have proved to be the wrong thing to do. During that period, most folks fled the actively managed mutual fund, particularly the domestic issues in favor of bond funds and in far too many instances, to target date funds.

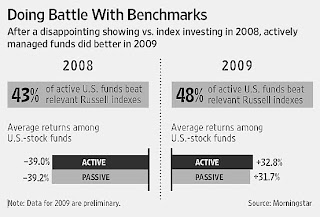

Let's consider the indices that are often compared to the riskier funds, a benchmark that has proven to be less than accurate in terms of performance. The Dow and the S&P 500 track the largest companies, a group that has struggled to assure the investor that dividends and size were enough to best the market. Turns out, that picking and choosing, as actively managed funds do, would have been the better approach.

Two things come into play. One, these funds tend to have higher fees. Less those fees, you would have still found yourself in a better position than had you simply put your money in a benchmark S&P 500 index.

And secondly, there is the liquidity issue that comes with buying mid-cap and small-cap companies. Liquidity refers to the amount of stock available in smaller companies weighed against the amount of stock held by the principals. This makes these companies more volatile and even under-purchased in indexes that track those larger markets (the Wilshire 5000 for instance may track all available stocks but the indexes crafted based on this index only own.

To complicate matters somewhat, the Wilshire 5000 actually has 5700 stocks in the index, Wilshire 4500 is the Wilshire 5000 without the S&P 500 stocks in it. A Wilshire 5000 index fund (usually called total market index) will probably own around 4000 stocks. A Wilshire 4500 index contains those same stocks less the top 500 companies.

As Mark Hulbret noted in a recent column for Marketwatch, "According to a report produced earlier this week by Lipper (a Thomson Reuters company), 45% of the domestic-equity funds for which they have data back to October 2007 were, as of the end of May, ahead of where they were on the date of the stock market’s all-time high."

So the indexes are lower than where you would have been had you stayed put - of course this is based on the assumption that many of you where using actively managed funds in your 401(k) plans, that many of those funds did not have indexes available and the post 2007 products such as target date funds or even ETFs, weren't a consideration or even an option during those days. You embraced risk and ignored fees and looking at your portfolio, that was probably seen as a good thing.

Does that mean index funds shouldn't be part of your portfolio? The simplest answer is no. Index funds still provide a low cost and low turnover environment to invest in. More importantly, the largest cap indexes add dividends to the mix. This brings these investments closer to the domestic out-performance over the last half of the year.

Diversity in this investment environment, which is still far more volatile than anyone would like it to be, with global issues remaining a major concern, means taking a little less - in terms of performance. You should be in index funds now. To do this would be considered a defensive move for those that kept the actively managed faith.

A portfolio of five, perhaps six index funds, tracking sectors from the S&P 500, a mid-cap index, a fund tracking the small-cap, an international index (which tracks the companies of what is considered the developed world), an emerging markets index (contains investments from countries like China, India, Russia, Brazil and others) along with a bond index. This sort of diversification keeps the low cost features of index funds and avoids any crossover investment (owning the same stocks in different funds).

You can be proud of your investment accumen in getting back to those 2007 highs and perhaps beyond. But show your real prudence and protect what you have done. This economy, both domestic and globally is far from recovered and the stock market is painting a better picture than reality suggests. Being a little defensive at this juncture will keep you in the game without risking what you have gained.

But you would have been much better off had you done absolutely nothing. Back in those desperate times, many people did what the rest of the herd did as stocks began to tumble. You sold. But three years later, that would have proved to be the wrong thing to do. During that period, most folks fled the actively managed mutual fund, particularly the domestic issues in favor of bond funds and in far too many instances, to target date funds.

Let's consider the indices that are often compared to the riskier funds, a benchmark that has proven to be less than accurate in terms of performance. The Dow and the S&P 500 track the largest companies, a group that has struggled to assure the investor that dividends and size were enough to best the market. Turns out, that picking and choosing, as actively managed funds do, would have been the better approach.

Two things come into play. One, these funds tend to have higher fees. Less those fees, you would have still found yourself in a better position than had you simply put your money in a benchmark S&P 500 index.

And secondly, there is the liquidity issue that comes with buying mid-cap and small-cap companies. Liquidity refers to the amount of stock available in smaller companies weighed against the amount of stock held by the principals. This makes these companies more volatile and even under-purchased in indexes that track those larger markets (the Wilshire 5000 for instance may track all available stocks but the indexes crafted based on this index only own.

To complicate matters somewhat, the Wilshire 5000 actually has 5700 stocks in the index, Wilshire 4500 is the Wilshire 5000 without the S&P 500 stocks in it. A Wilshire 5000 index fund (usually called total market index) will probably own around 4000 stocks. A Wilshire 4500 index contains those same stocks less the top 500 companies.

As Mark Hulbret noted in a recent column for Marketwatch, "According to a report produced earlier this week by Lipper (a Thomson Reuters company), 45% of the domestic-equity funds for which they have data back to October 2007 were, as of the end of May, ahead of where they were on the date of the stock market’s all-time high."

So the indexes are lower than where you would have been had you stayed put - of course this is based on the assumption that many of you where using actively managed funds in your 401(k) plans, that many of those funds did not have indexes available and the post 2007 products such as target date funds or even ETFs, weren't a consideration or even an option during those days. You embraced risk and ignored fees and looking at your portfolio, that was probably seen as a good thing.

Does that mean index funds shouldn't be part of your portfolio? The simplest answer is no. Index funds still provide a low cost and low turnover environment to invest in. More importantly, the largest cap indexes add dividends to the mix. This brings these investments closer to the domestic out-performance over the last half of the year.

Diversity in this investment environment, which is still far more volatile than anyone would like it to be, with global issues remaining a major concern, means taking a little less - in terms of performance. You should be in index funds now. To do this would be considered a defensive move for those that kept the actively managed faith.

A portfolio of five, perhaps six index funds, tracking sectors from the S&P 500, a mid-cap index, a fund tracking the small-cap, an international index (which tracks the companies of what is considered the developed world), an emerging markets index (contains investments from countries like China, India, Russia, Brazil and others) along with a bond index. This sort of diversification keeps the low cost features of index funds and avoids any crossover investment (owning the same stocks in different funds).

You can be proud of your investment accumen in getting back to those 2007 highs and perhaps beyond. But show your real prudence and protect what you have done. This economy, both domestic and globally is far from recovered and the stock market is painting a better picture than reality suggests. Being a little defensive at this juncture will keep you in the game without risking what you have gained.